Themis J. Michailides & Victor Manuel Gabri, University of California, Davis / Kearney Ag Research and Extension Center

In the last several years, walnut growers in California experienced unusually high levels of mold in their crop. Particularly in 2018, growers in Glenn and Butte counties reported 30-40% mold. Levels of 1-3% mold are considered something the growers expect in a normal year.

Definition of mold

According to the US Standards for grades of walnuts in the shell, mold is one of the seven types of damage which when is attached to the kernel and conspicuous; or, when inconspicuous white or gray mold affects an aggregate area larger than 1 square centimeter or one-eighth of the entire surface of the kernel, whichever is the lesser area.

Characteristics of nuts affecting mold

Initial reports of the 1970s and 80s reported Penicillium spp. causing mold, but in recent years, the predominant fungi isolated from walnut kernels with mold are mainly species of Fusarium and Alternaria. In years with unusually long drought and hot weather Aspergillus niger can also cause mold. Also, in orchards where there is Botryosphaeria and/or Phomopsis canker and blight, Botryosphaeria and Phomopsis fungi can also invade the walnut cavity and cause mold. When isolates of Alternaria and Fusarium fungi were inoculated on walnut fruit, this resulted in mold covering the infected kernels. Back in 1994 and 1995, Drs. M. Doster and T. Michailides cracked about 4,000 walnuts and determined levels of mold after separating them in various categories. In those studies, it was found that nuts had more mold when a) they were infested by the navel orangeworm and/or other insects; b) when nuts were damaged by sunburn; c) nuts had shriveled husks and/or had decay lesion on their hull; d) when the opening of their ostiole was larger than smaller; e) nuts were larger size than smaller size; and f) when nuts stayed on the ground more than 24 hours before harvest (i.e., windfalls, etc.)

Infection and other factors affecting mold levels

After opening mature nuts and examining the origin of the fungal colony as it developed on the kernel, up to 80% of the fungal colonies originated from the stylar end, while up to 30% originated from the stem end. This suggests that a high level of mold from fungal infection occurs at the style of the flower/young developing fruitlet.

To check this hypothesis, samples of walnut flowers were collected and the flower style was plated on agar media. The predominant fungi isolated were Alternaria (up to 38%) and Fusarium (up to 12%). Among the serial inoculations of walnut with Alternaria or Fusarium, the inoculations at the end of April (bloom time) resulted in significantly more infection by Alternaria (57%) or Fusarium (55%) than the water-inoculated control. These results suggest that indeed a high incidence of mold infection starts during bloom of walnut. Infections also can occur at later stage as well, particularly close to and after the hull split stage of fruit.

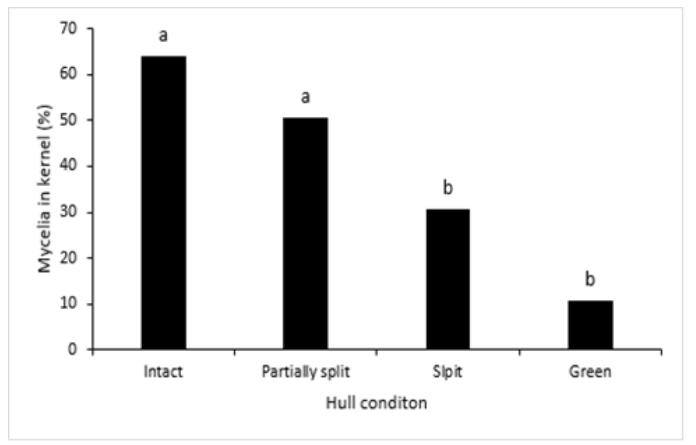

Depending on the time of infection, infected nuts show different characteristics. The nuts that are infected at bloom, when the mold develops sooner, result in infected nuts with brownish, wrinkled and intact hulls (without any cracks). Nuts that are infected at the early hull-split stage will have cracked (partially split) hulls. Nuts that are infected at a later hull-split stage will have black hulls and entirely split hulls that develop sections connected at the stem end. Of these nuts, more mold was found in the earlier-infected nuts (those with intact, but shriveled hulls and partially cracked hulls) than in the later-infected nuts (nuts that were black and had entirely split hulls) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Incidence of fungal mycelia in the kernel of “black” blighted (moldy) by category of various types of brown/black- and green-hull nuts, depending on the condition of their hulls, intact wrinkled brown hulls; partially split (brown) hulls; and black with well split hull sections. (Bars topped with different letters are significantly different according to an LSDA test (P = 0.05).

Mold management

Cultural practices

Although controlling relative humidity in the orchard is not easy, avoid having puddles of water in the orchard to decrease humidity. Also, because Alternaria and Fusarium are airborne fungi, be careful about creating dust, especially during bloom and hull split, to reduce inoculum that can infect flowers and hull split nuts.

Fungicide sprays

One spray with flutriafol (Rhyme) at a rate of 7 oz /acre 1-3 weeks before hull split (HS), or at 20-30% HS, resulted in a 60-70% reduction of mold in a Chandler orchard in Butte Co.

In another experiment in 2023, Chandler trees in a flood irrigated orchard were sprayed with Luna Experience at 17.0 fl oz/acre with three different timings: 1) one spray at bloom, 2) one spray at bloom and one spray 1 week before hull split or 3) two sprays, 3 and 1 weeks before hull split. All treatments reduced blighted (moldy) nuts by 40 to 55%, and there were no significant differences whether the trees received one or 2 sprays.

In 2024, in the same flood-irrigated orchard was treated with different fungicide combinations at different times. One spray with Luna Experience combined with Ethephon applied at 20-30% HS reduced blighted (moldy) nuts the most by 54%. Other treatments reduced mold by 40- 48%: One Luna spray alone at 20-30% HS, one Luna spray 1 week before HS, or Ethephon only spray alone at 20-30% HS. All the spray treatments were significantly lower than the untreated control, but they did not differ between each other.

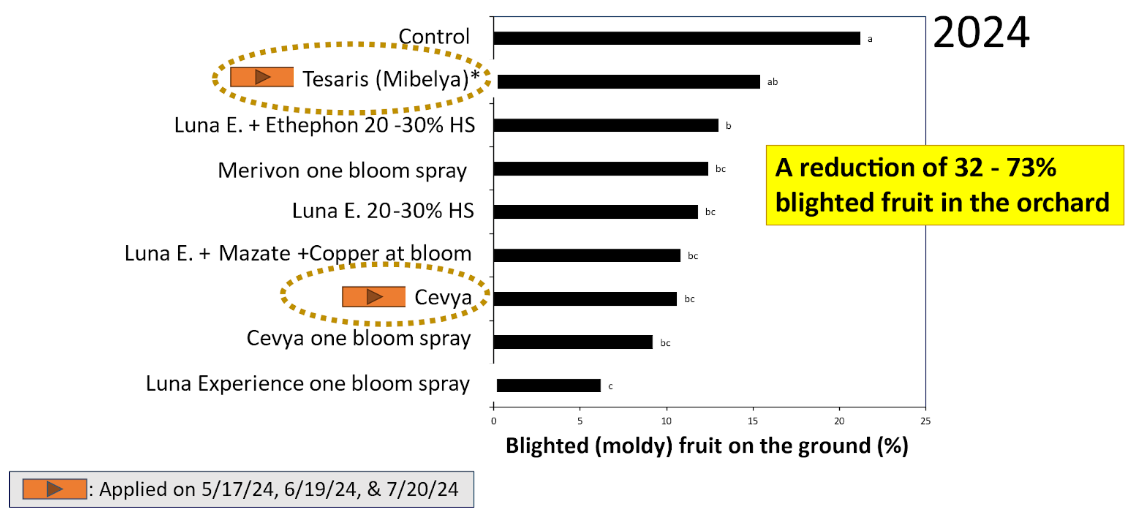

Also in 2024, in a sprinkler-irrigated Chandler orchard with heavy Botryosphaeria canker and blight, one bloom spray with Merivon, Cevya, or Luna Experience each significantly reduced blighted (moldy) nuts by 43-73%. All the sprays as described in Figure 2 showed significantly lower blighted (moldy) nuts than the untreated control. In this orchard, Botryosphaeria canker and blight was severe, and >75% of the moldy nuts had Botryosphaeria species isolated from them causing kernel mold. The results suggest that a new fungicide (Cevya, FRAC 3) can be added as a tool for walnut growers for the control of Botryosphaeria canker and blight and mold.

Figure 2. Effect of fungicide sprays on Botryosphaeria moldy nuts recorded in the field after tree shaking in a sprinkler-irrigated Chandler orchard in Butte Co. Columns with different letters indicate significant differences according to an LSD test (P = 0.05).

For more information consult the 2024 Project Report to the California Walnut Board by Michailides et al.

Leave a Reply