Jaime Ott, UCCE Farm Advisor, Tehama, Shasta, Glenn, and Butte Counties

According to Dr. Jim Adaskaveg, UC Riverside professor who has been studying walnut blight for decades, these are the most common mistakes growers make in their blight control program:

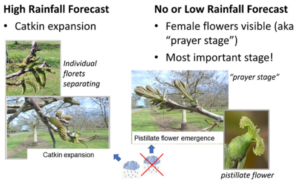

Figure 1. In orchards with low levels of walnut blight in the last few years, the weather during bloom is the most important factor when deciding when to start your blight spray program.

Walnut blight is caused by the bacterium Xanthomonas arboricola pv. juglandis (Xaj) and is one of the most devastating diseases in walnut orchards. Xaj overwinters in bud scales and infects young flowers and shoots as they emerge in the spring. Rainy weather favors infection, and nearly any young tissue exposed to water (rain, dew, sprinklers) is susceptible.

Spray timing is crucial for effective management

Blight sprays protect young tissue from infection. It is critical to get the timing right on your spray: too early and the protection has worn off when it’s needed the most, too late and the infection has already happened. While weather is wet (conducive to disease), sprays will be needed every 7-10 days to protect new tissue as it emerges.

Spray coverage is crucial for effective management

The materials we use to manage walnut blight work as a protective layer: if tissue isn’t covered in your material, it is not protected from infection. Most of these materials are contact materials: they don’t move in the plant at all. Achieving excellent coverage should be your goal to make the most of the time and money you are investing in your sprays. Calibrate your sprayer to make sure you are getting the coverage you need for the protection you are counting on. Based on our experience in the field, half sprays just don’t provide good enough coverage for effective disease control.

Choosing the right mix of materials is crucial for effective management

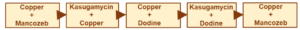

No single material effectively controls walnut blight. Historically growers have relied on copper, but copper resistance is common in Xaj populations throughout the state. In 2024, over 64% of the Xaj isolates Dr. Adaskaveg’s lab collected had genes for copper resistance. This resistance can be counteracted by adding mancozeb (Manzate) or dodine (Syllit) to the spray tank along with copper. Research by Dr. Adaskaveg has shown that similar levels of disease control can be achieved with much lower amounts of copper when mixing mancozeb, a copper hydroxide product (like Champ, at 32oz/Acre), and a copper sulfate pentahydrate product (like CS 2005, at 27oz/Acre). In this case, 16oz of metallic copper equivalent provided the same level of control as achieved with mancozeb + copper hydroxide at 64oz (32-oz metallic copper equivalent).

We also have access to the antibiotic kasugamycin (Kasumin), which is effective against blight when mixed with dodine, copper, or mancozeb. Kasugamycin is an important material for helping to manage copper resistance in Xaj. It is labeled for use in walnuts up to four times per season, with up to two consecutive applications before rotating to a different chemistry.

See the UCIPM Fungicide and Bactericide Efficacy Table for more information.

Figure 1. Example of a blight material rotation in a year with high rainfall during bloom and leafout. In this example, a grower would start with a copper + mancozeb spray at catkin expansion and apply each subsequent mixture at 7-10 day intervals.

*Any mention of a pesticide product is for illustration only and is not an endorsement or a pesticide recommendation, simply the sharing of research results. Consult your PCA and always read the pesticide label; the label is law.

Leave a Reply