Katherine Jarvis-Shean, UCCE Orchard Advisor, Sacramento, Solano and Yolo Counties

Allan Fulton, UCCE Irrigation & Water Resources Advisor Emeritus, Tehama, Shasta, Glenn, and Colusa Counties

With 41 California counties officially in a drought emergency and water allocations significantly reduced in many areas, many growers and managers are stuck with less water than walnuts use for prime production levels. In some crops (e.g. wine grapes, oil olives, almonds), water stress in certain developmental timeframes is not harmful, or may even be beneficial. Inducing this managed stress is called “regulated deficit irrigation” (RDI). Unfortunately, RDI is not an effective water saving strategy in walnuts. Sustained moderate to high water stress (stem water potential below -8 bars) at any growth stage will affect walnut crop productivity and quality.

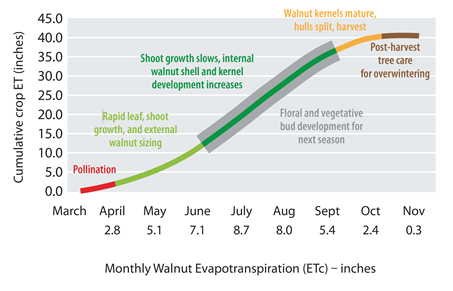

Different factors of walnut productivity are vulnerable to water stress depending on the timing and extent of that stress. Figure 1 shows the generalized water use from walnut as measured by evapotranspiration over the course of a growing season and the different stages of nut and/or shoot growth occurring in the same timeframe. Because shoots are growing and walnuts are sizing in May and June, water stress during this timeframe decreases shoot growth, which can decrease bearing wood for nuts the following year, as well as decrease nut size in the year of the stress. Because shells harden in June and kernels are developing in July, August, and September, water stress in this time can impact kernel size and quality. Because this is also the time that buds are developing for the following season, severe stress in this period can also reduce flowers for nuts the following year.

Figure 1. Cumulative and monthly average walnut evapotranspiration, tree growth and nut development over the growing season. (Fulton & Buchner, 2015)

When faced with less water availability for irrigation, it is worth checking on system distribution uniformity to be sure the limited water that you do have is going exactly where you want it to go. An irrigation system that has not been maintained can apply twice as much water close to the pump as at the end of the system lines. Check out UC ANR’s maintenance of microirrigation systems site and our article on Irrigation System Maintenance for guidance on how to check system pressure uniformity, flush irrigation lines and manage emitter clogging.

Once you are confident your system is applying water uniformly, the next water saving step is to be sure you’re not applying more water than the trees need, and not moving that water below the rootzone where the trees can’t access it. Irrigating based on evapotranspiration losses from the orchard is a relatively simple approach to manage this concern. Crop specific weekly ET totals can be found on the Sac Valley Orchards ET page, where you can subscribe for weekly emails. Alternatively, you can contact your local UCCE office to sign up for weekly emails (Kat Jarvis-Shean for southern Sac Valley and Curt Pierce at calpierce@ucanr.edu for northern Sac Valley). Numbers from ET reports give water use estimates for a generic, mature orchard based on local weather station data.

However, using a pressure chamber to directly measure tree stress via stem water potential is the most precise way to gauge the stress orchard trees are experiencing. Sac Valley Orchards has a series of how-to guides on measuring and interpreting stem water potential for everyone from beginners to long-time users. Finally, soil moisture sensors at different depths can help monitor and prevent irrigation set lengths that push water past the bottom of the zone of concentrated roots, generally around three feet deep.

Even with a highly uniform system and precise irrigation accounting for the climate, soil, and tree measurements, reducing applied water to stressful levels may be unavoidable. During the last drought Allan Fulton and Rick Buchner, Farm Advisors Emeriti, created a drought strategies guidance document to explain different strategies and expected outcomes depending on the level of irrigation reduction. Since the 2015 document, we have learned that pressure chamber use in spring can be used to safely delay the start of irrigation. Lessons learned from this new research have been integrated into the different strategies and expected outcomes depending on the level of irrigation reduction outlined below.

| Percent Reduction | Percent of ET Applied | Water Shortfall | Strategy | Expected Outcome |

| 20% | 80% | 4-8” | Assess refill of soil water storage during the winter. Look for evidence that effective rainfall was sufficient to recharge root zone at least four or five feet deep. If winter rainfall has been too low, consider some winter irrigation to compensate. Delay the start of irrigation until -8 bars. Depending on the orchard and soil setting, the timing of the first irrigation may be delayed considerably. | Stored water can be relied upon to help manage limited water supply during the growing season. 20 to 30 percent water/energy savings. Minimal impact on shoot growth and bud development. Slightly (10%) reduced external nut size and nut weight but edible kernel may actually be higher which positively affects nut value. |

| 21-50% | 50-79% | 8-21” | Continue to save water early in the season by waiting until -8 bars to apply the first irrigation. Allow more stress prior to irrigation from kernel development through postharvest, up to -10 bars. Prioritize water to higher producing orchards over orchards that are near the end of their productive life. | Higher percent dark kernels in addition to smaller nuts. Lower edible kernel yields, decreased fruit bud development and thus lower yields next year. |

| 51-100% | 0-49% | 21-42” | To the extent possible, apply stress uniformly throughout the season and try to maintain -8 to -12 bars stress. Save enough water for post-harvest irrigation to help guard against frost and cold injury in autumn. | Expect severe impacts to nut size and quality. In this range, the objective is tree survival. Expect at least severe impacts on shoot growth, bud development, and two years of normal irrigation before return to higher (better, more normal) yields. |

Leave a Reply