Since mid-April, many advisors up and down the Valley have been receiving calls about unusual leaf-out in pistachio and walnut. The Sacramento Valley has certainly been experiencing this.

In pistachios, we have seen straggled leaf-out, particularly in the Kerman and Peters varieties. When I surveyed a number of Kerman orchards in Yolo County on April 24 with a PCA, we saw many trees with growth on the tips of shoots and no growth farther down the branch, sometimes known as “poodle tail” growth (Figure 1). In many orchards, instead of the poodle tale growth we saw growth low in the canopy and bare wood higher up. When we cut into branches, they were green and healthy. Most vegetative buds were green but not swollen, indicating they would not push anytime soon.

Figure 1. “Poodle tail” leaf-out, with growth only on the tips of branches. ‘Kerman’ pistachio, April 24th, Yolo County. Photo: Kat Jarvis-Shean

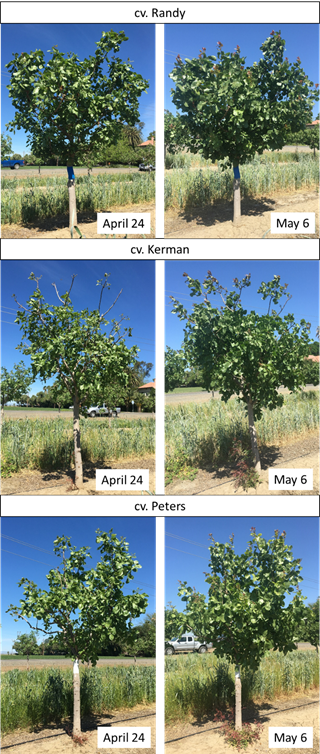

Interestingly, in the first orchard severity of symptoms varied with terrain, with trees in high spots showing less growth than trees in low spots. The ‘Golden Hills’ orchards we looked at were more progressed in their leaf-out, but looking closely you could see that most of the canopy leaves were on terminal growth, with large sections farther down the branches where buds that had not broken. In orchards with multiple male varieties, ‘Randy’, showed less bare wood and fewer unbroken buds than ‘Kerman’ and ‘Peters’ (Figure 2). Often, but not always, ‘Peters’ showed worse symptoms than ‘Kerman’.

Figure 2. Leaf out of three cultivars (‘Randy’, ‘Kerman’ and ‘Peters’) in one orchard. Note the more filled canopy in ‘Randy’. Photos: Kat Jarvis-Shean

In walnuts, similar symptoms have been found. In young Chandler and Howard walnuts in Yolo, Solano and Sutter Counties, trees showed “poodle tail” growth, as well as more growth in the lower third of the canopy (Figures 3, 4 and 5). In older orchards, which often have a high percentage of spurs killed by Botryosphaeria, it is hard to discern from the ground if buds are delayed in breaking or are simply dead. However, in many older orchards, growth was sporadic throughout the canopy. Some branches had fully expanded leaves while others had little-to-no budbreak. Often, but not always, there was more growth in the lower third of the canopy.

Returning on May 6th, the difference in leaf out timing manifested in a large variability in walnut fruit size in mature trees, from the size of quarter to barely the length of Thomas Jefferson’s ponytail on the nickel (Figure 6). Note that Luke Milliron has also documented upper-canopy freeze damage in Butte County recently. This looks slightly different. With this freeze damage, there is a lack of growth on the entire shoot, whereas we are most often seeing growth on the shoot tips and lack of growth below that.

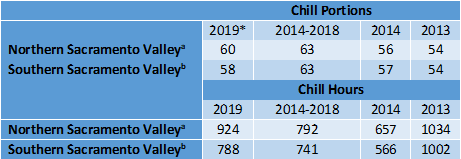

Why are we seeing these symptoms? We know that deciduous trees like pistachios and walnuts need to experience a certain accumulation of winter chill accumulation, followed by a certain accumulation of spring heat, to break dormancy and bloom and leaf out in the spring. The prolonged and scattered leaf-out we’ve seen is consistent with the trees having problems breaking dormancy, with higher chill requirement varieties often showing more extreme symptoms. This is somewhat surprising, because though this was not a boom year for winter chill accumulation, it was not a bust year either. I calculated chill accumulation back in mid-February (Table 1). When using chill portions, the average chill accumulation for the 2019-2020 winter (“2019” hereafter) in the northern Sacramento Valley was 4% below the average for 2014-2018, but still 9-11% above our most recent low chill winters of 2013 and 2014. Chill accumulation in the southern Sacramento Valley was 8% below the average of 2014-2018, but still 2-8% above the most recent low chill winters. When chill accumulation was counted using the simpler, older chill hours model, both the northern and southern Sacramento Valley were ahead of the 2014-2018 average, and hundreds of chill hours higher than the low chill winter of 2014.

Table 1. Regional averages of winter chill accumulation (November 1-February 19) in the Sacramento Valley in recent years calculated using temperature records from the California Irrigation Management Information System (CIMIS).

Note: Some CIMIS stations were excluded because of data quality concerns.

* Years given represent the beginning of winter. For example, “2019” represents the winter of 2019-2020.

A. Biggs, Durham, Williams, Gerber stations (except 2013, for which Biggs and Williams were not available)

B. Twitchell Island, Winters, Verona, Woodland, Davis stations

Thus, though the growth habit we are seeing in the field is consistent with low winter chill accumulation, the story may be slightly more complicated. UCCE Farm Advisor Craig Kallsen in Kern County has suggested that part of the issue may be cool temperatures as we were just getting into bud break. He documented cool temperatures occurring together with stalled growth in many pistachio orchards. It is also worth remembering that we count winter chill using air temperature as a proxy for tree temperature, and some years that proxy is more accurate than others. It may be that the chill we counted was less effective because limited cloud cover and fog this winter resulted in the trees receiving more direct, warming solar radiation. Research by Dr. Maciej Zwieniecki has been finding that warm winter temperatures contribute to burning down carbohydrate reserves in trees, which then interferes with vigorous and timely budbreak.

What can be done about this? Whatever the cause of these budbreak issues, from a management perspective for this year, the best course of action is inaction. It may be tempting to prune trees to try to force growth. However, returning to the same trees I visited on April 24th, I found canopies were starting to fill in (Figures 2, 3, 4). Certainly, there was still plenty of bare wood, often obscured by terminal bud growth. However, buds on these bare sections of shoots are still green and alive. Many buds are just now starting to push (Figure 7 and 8), and will likely continue to push growth through May.

Leave a Reply