Luke Milliron, UCCE Farm Advisor, Butte, Tehama, and Glenn Counties; Bob Johnson, PhD Candidate Rizzo Lab, UC Davis Plant Pathology

In March of 1995 a four-day storm with winds reaching nearly 65 mph and a deluge of six-inches resulted in an estimated 15,000 acres of downed almond trees in California, with losses at the time calculated at $210 million. Joseph Connell (UCCE Butte) and Dr. Jim Adaskaveg (Plant Pathology, UC Riverside) surveyed downed trees and categorized the potential predisposing factors. Part of the study’s findings were that white rot fungi may have played a role in tree loss. They observed basidiocarps (fruiting bodies) of Oxyporus spp., Phellinus gilvus, Ganoderma brownii, and Gloeoporus dichorus associated with a portion of the downed trees. This study was key to the understanding that wood-decay fungi can contribute to serious tree losses during winter storm events.

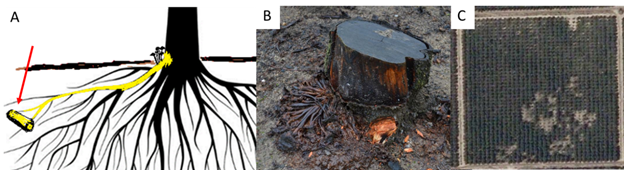

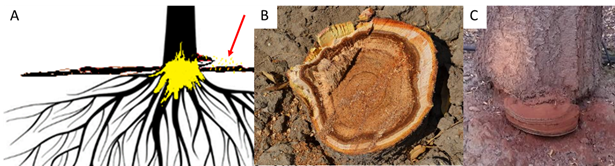

Twenty years later, Bob Johnson, a graduate student in the department of Plant Pathology at UC Davis, began research into wood-decay fungi in almonds. In 2015 he set out to survey California’s almond growing regions and identify the main wood-decay fungi associated with windfall. Ganoderma species were identified as the primary cause of decay in windfall trees, specifically G. brownii and G. adspersum. These decay fungi cause internal decay from the butt, or base of the trunk (near soil level) and invade upwards, often remaining completely undetected before the windfall event.

Wood-decay infections by part of the tree: roots, butt and roots, and scaffold:

Ganoderma butt rot: Young orchards prevalent in new survey’s windfall losses:

As Johnson communicated with growers about his efforts, he began receiving reports of windfall trees to investigate. Most disturbingly, many of the calls concerning windfall were reporting losses in young, otherwise healthy trees. Previously the consensus was that wood- decay fungi were non-aggressive and were secondary pathogens most often associated with older orchards. For example, in the 1995 survey, Lovell rooted almond orchards had windfall loses between 6.2% and 20% for four orchards ranging in age from 15-21, versus 3.3% loss in the youngest (8th leaf) orchard. Reports of windfalls of trees in older orchards have continued, and in these cases G. brownii, one of the species from the 1995 survey, is often the problem. However, Johnson has also received reports of extensive windfall losses in orchards as young as seven years old. In these cases he has identified G. adspersum, which had not been previously been reported in California. These losses have been so severe in several cases that orchards as young as 10 years old have been completely removed following the extensive losses. Thankfully for Sacramento Valley growers, all of the orchards with G. adspersum infections have been identified in the middle to southern San Joaquin Valley.

Why the more aggressive G. adspersum has not been discovered in the Sacramento and Northern San Joaquin Valley is a mystery. Perhaps more fungal diversity and competition of both pathogenic and benign fungi in our historical orchard growing region has prevented widespread G. adspersum infections. But most likely, this species, which is native to Europe, has not yet made its way north to the Northern San Joaquin and Sacramento valleys.

Researching how infections occur and how they can be managed:

The latest wood rot research has focused on how the infections are taking place, and what management tools are available. The current theory for these fungal infections is that trees are predisposed to infection through wounds at or below the soil line, inflicted during harvest or winter sanitation shaking. Windborne spores are then dispersed during sweeping and pickup harvest operation with subsequent irrigation allowing spores to percolate into the soil and germinate. Since this route of infection is unavoidable in current almond production, Johnson has focused on testing rootstock susceptibility and efficacy of commercially available biological materials (i.e. Trichoderma spp.) that may out compete the wood-decay fungi. Theoretically removing the conks (fruiting bodies of wood-decay fungi) may also help, especially if those conks, which can sporulate year-round, happen to be active during harvest operations.

Sacramento Valley growers have so far been spared from the most aggressive wood-decay induced windfall losses. However, this may not always be the case. Growers should carefully evaluate tree losses due to windfall, particularly in younger orchards, for the presence of internal rotten wood at the butt or site of branch breakage. If you suspect wood-decay fungi led to windfall losses in your young almond orchard, please contact your local UC Cooperative Extension farm advisor.

Leave a Reply