Ryan J Hill, UCCE Tehama County, Agronomy and Weed Science Advisor

Preemergent herbicides are a valuable tool in an orchard’s integrated weed management plan. If you survey a room full of growers, you will get answers across the board as to when it is best to apply preemergent herbicides in almonds. Do you apply after harvest to stop those early emerging winter weeds? Do you wait until late winter/early spring to get ahead of the summer annuals? What about rates? Is it better to apply a high rate in winter or multiple applications at a lower rate? These are all good questions and the best answers usually differ from farm to farm. Weed populations vary and so should management choices.

Waiting to apply until early spring may save some costs and it also may be effective enough for your needs. As the rains stop and irrigation resumes it is absolutely essential to keep sprinklers unobstructed and to reduce weed competition in your orchards. The chaos of the growing season makes it easy to miss weed control timings if things get out of hand. Having a good residual herbicide holding off new flushes of germination can be a lifesaver and spring-applied preemergents have a better chance of lasting through the summer season than winter applications. However, waiting to apply preemergents until spring means you may have winter weeds growing when the herbicide goes down. Some preemergents have no effect on emerged weeds so you will need to consider including a good postemergent treatment to target weeds that already emerged. This essential component of the spring application brings up two major considerations:

First, if coverage of winter annuals is dense, you could be left with a mat of thatch after your clean up treatment. Thatch can interfere with effective preemergent application, binding up the herbicide in the dead organic matter before it reaches the soil. The picture below shows the results of a spring application of Matrix (rimsulfuron) or Prowl (pendimethalin) intended to control johnsongrass seedlings (both products are labeled for this weed) in a heavy thatch situation in an orchard. Bermudagrass is the only weed left in the Matrix plots, but in the Prowl plots johnsongrass control was much lower, likely because the thatch prevented herbicide from reaching the soil where the seeds were germinating. Pendimethalin, the active ingredient in Prowl, binds tightly with organic materials (leaves and living or dead weeds) and this can affect its performance in settings like this. Thatch is not typically quite this thick in almond orchards, but the plots shown below demonstrate the principle.

Second, postemergent clean-up treatments may not be as effective as expected if you have herbicide resistance in your field. Herbicide resistance in winter annuals like hairy fleabane and Italian ryegrass will most likely remove some postemergent herbicide options from your toolbox.

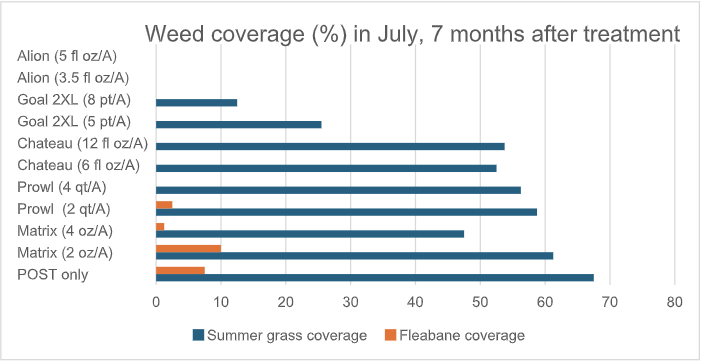

If this second point is true of your operation, consider applying preemergent herbicides in the fall before germination of these species. Both hairy fleabane and Italian ryegrass are typically very sensitive to preemergents. Last season I installed a trial demonstrating the effect of several preemergent herbicides (though this list is not exhaustive) applied in December on hairy fleabane populations. All treatments were tank-mixed with postemergent herbicides to control weeds that had already germinated, and one plot received only the postemergent treatment (“POST only”, at the bottom of the graph). Below are the weed coverage numbers (averaged across 4 replications) from July, seven months after treatment.

The summer annual grasses were coming on strong by July and you can see from the figure that only Goal and Alion were still having any effect reducing weed coverage by then. This doesn’t mean Matrix, Chateau, and Prowl are not useful herbicides, but their residual activity simply does not last a full seven months. Hairy fleabane was controlled by most treatments that included a preemergent (Prowl is not labeled for control of fleabane). If another preemergent herbicide application was included in the spring to control those summer annuals, I expect this field would have seen season-long control in most plots.

Matrix (rimsulfuron) is labeled for control of hairy fleabane so I was curious to see so much fleabane in my Matrix plots. It is possible, though not certain, that this is an example of herbicide resistance, particularly since this herbicide had been used repeatedly in this field in the past. Rimsulfuron, the active ingredient in Matrix, has a group 2 mode-of-action, and group 2 herbicides are the greatest offender worldwide for herbicide resistance. Herbicides are classified by the Weed Science Society of America based on what they target in the weed and all group 2 herbicides target the same protein. If you are using products in this category, be sure to follow careful resistance management practices. This means not using the same type of herbicide to control the same weed year after year (look at the herbicide label to see what group number you are using). Switching through different groups is referred to as rotating herbicides.

The above trial demonstrates that very few preemergents can be applied in winter at a high rate and keep an adequate level of control through harvest. Relying too often on one or two very strong preemergents is a recipe for herbicide resistance. Weeds can also develop resistance to preemergent herbicides! Indeed, all herbicides come with the risk of resistance. Applying different preemergent treatments at lower rates in both winter and spring can give long-term control while also following good resistance management principles, as seen this article from Brad Hanson and Caio Brunharo for more information on split application timings click here.

Leave a Reply