Katherine Jarvis-Shean, UCCE Farm Advisor, Yolo, Solano, & Sacramento Counties

Joseph Connell, UCCE Farm Advisor Emeritus, Butte County

Almond orchards are a multi-decade investment. No one can be exactly certain what the future holds, but orchard development requires that we make decisions with the best information available. While there are plenty of moving parts to that decision-making – global markets, labor cost and availability, SGMA, state and regional regulations, etc – part of that decision-making process requires thinking through what growing conditions are expected to be like in the next 20-30 years. Recent years have brought hot temperatures, heat waves, droughts and rain that have broken records. Research is finding that we should plan for more of these types of years in the next few decades, and expect future growing conditions in the Central Valley that will be warmer and both wetter and dryer. What does that mean? And what can we do to plan for it?

Warmer Temperatures

This summer was California’s hottest summer on record according to the National Weather Service, with many locations in the Sacramento Valley breaking one-day records and heat wave records. While we haven’t had a consistent progress of record-breaking summers in a row, we are seeing more of them. This is in keeping with what research is telling us to expect. It’s not expected that every year will break temperature records. We’ll continue to experience cool spells and hot spells, but the cool spells will be a little less cool, and the hot spells will be even hotter.

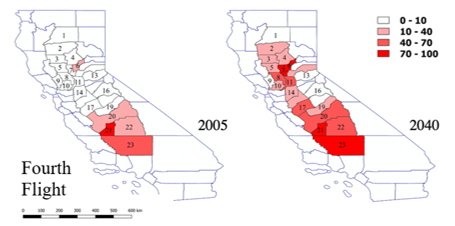

Summer temperatures are expected to increase, on average, about 2° F in the next 20-30 years. Scientists expect at least 50% more extreme heat days in the summer, and at least a 40% increase in the number of heat waves (3-4 or more extremely hot days in a row) (see links 1 & 2 below for details). This will translate to higher amounts of water use by trees through increased transpiration and worker safety issues, among many other concerns. This will also translate to more growing degree days for pests in our orchards. As UC IPM Advisor Jhalendra Rijal discussed on a recent Growing the Valley UC podcast, these warmer summer temperatures, along with earlier biofixes from warmer springs, will result in seeing four flights of navel orangeworm much more frequently in the Sacramento Valley (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Increase in frequency of NOW fourth flight between 2005 and 2040. Darker red indicates higher percentage of years in which fourth flight will occur. Adapted from Pathak et al. (2021)

Wetter and Dryer? How is that possible?

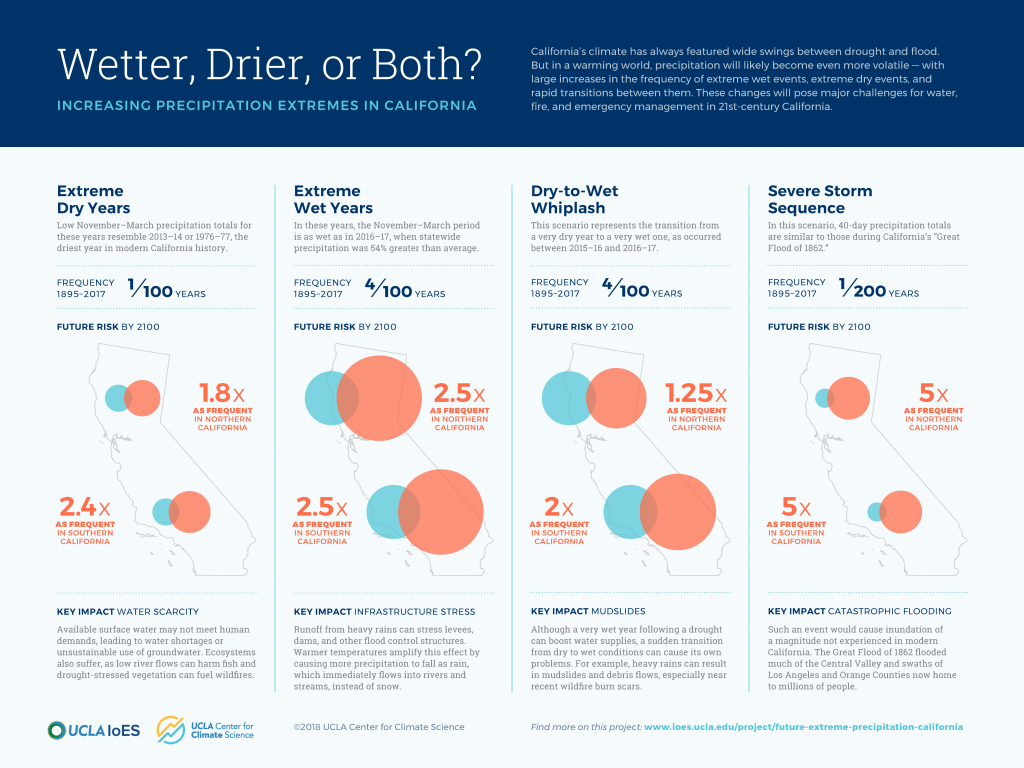

There’s been no rest for the weary when it comes to seasonal rainfall total in the last few years. We went from the historic drought of 2012-2016 to record-breaking rainfall the winter of 2016-2017, to the last two dry winters that have many reservoirs and water tables crying Uncle. Scientists call this ‘precipitation whiplash’, and as Daniel Swain explained on a recent Growing the Valley UC podcast, we should plan for continued whiplash in the future, with both more extremely wet winters, and more extremely dry winters (Fig 2).

In the coming two decades, scientists expect Northern California will have about 50% more extreme wet seasons (similar to the winter of 2016-2017) than we had in the ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s. But also in the coming two decades, scientists expect an increase in extremely dry rain seasons (slightly drier than 2013-2014), about 25% more than what we had in the ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s. It’s also expected that falls and springs will be dryer, meaning our rainfall, when we get it, will be compacted into fewer months. So, if you’re looking at decade averages, our rainfall averages will be about the same as the past, but on a year-to-year level, we’ll be experiencing more wet years and more dry years. The silver lining of these increased wet years is they should make multi-year droughts become less frequent. You can read more about this research here: https://weatherwest.com/archives/6252.

Fig 2. Scientists expect increases in both extreme wet years and extreme dry years. Adapted from https://weatherwest.com/archives/6252 & (3) below.

So, What Does This All Mean for Orchard Planning?

Put together, this means almond orchards planted in the next few years (and the recent past) will experience more extremes in wet and dry winters than orchards that came before them, along with more extreme heat, and more pest pressure. This will all occur under a more watchful eye when it comes to groundwater use, and likely more limitation and less efficacy from our traditional pest management tool box. Growers and advisors will continue to find innovative ways to adapt to these challenges, but here are a few things to consider:

For reduced water availability…

- How old are the orchard blocks in your portfolio? Is a block coming into production and will it be experiencing its best years in the future, or is it older and likely to experience higher costs and gradually lower production? Prioritize the most productive blocks for receiving available water and possibly remove the blocks that are over the hill to concentrate available water on the best orchards.

- What about varieties and the costs and returns for managing a particular orchard? Some varieties have experienced price discrimination compared to the premium Nonpareil variety. Blocks of semi-hardshells have lower costs related to pest management and harvest but they may also have lower returns. What does the overall economic situation of the block look like? Consider the profitability of each block on a cost and return basis. If there are some orchards that are likely to be less profitable in an ongoing way, those are the blocks that must be sacrificed if there is insufficient water to take care of the entire operation.

- Rootstocks differ in their ability to withstand drought and water cutbacks. Peach-almond (PA) hybrid rootstocks such as Hansen. Brights 5, Nickels and Titan are generally more drought tolerant, likely because they have a larger root system that can access more soil moisture. They are also more tolerant of higher levels of chloride and other salts often found in poor quality irrigation water than Lovell, Nemaguard, or Krymsk 86. If water is cut back, or available in only a minimal amount, a PA hybrid block should survive better and recover quicker than other rootstocks.

- Plan for changing groundwater levels, and make it easier on yourself to adapt when that happens. Have a flow meter and pressure gauge on your pump so you can know when changes are happening in your system. Set your orchard up for easy regular system maintenance. Consider a back-up plan when your system pressure drops, like manifolds to divide blocks more easily to irrigate smaller sections and keep pressure higher, variable speed pumps or the ability to drop bowl depth.

When water is over-abundant…

- Know your soils maps, where you have infiltration issues and access problems during wet winters. Consider prioritizing these areas when doing tree training, NOW sanitation, or other winter tasks that require orchard foot traffic.

- Think about soil amendments, cover crops, or resident vegetation to increase infiltration in your soils compared to bare orchard floors. Leaving a cover crop or resident vegetation in your middles will provide a significant improvement in both rainfall and irrigation infiltration.

- If, given your soils and water access, you expect too much water to be a harder problem to solve than too little water, consider rootstocks with Myro plum background, such as Krymsk 86, that often have shallower roots and better tolerance (though not total invulnerability) for wet feet.

- Plan for rapid runoff of excess water and to support crown health. During site development of relatively flat sites, consider laser leveling if the site is relatively flat and raise the tree crowns above the soil level by planting on berms, islands or mounds to reduce Phytophthora

For warmer temperatures…

- Navel Orangeworm is an ongoing pest management issue with possibly increasing pressure. Consider the vulnerability of different varieties, in terms of shell seal and stick tights that lead to mummy build up. Also, earlier maturing varieties are less exposed to higher pressure of the later NOW generations compared to mid to late maturing varieties. Consider starting to work with mating disruption as an extra tool in the NOW tool kit.

Each orchard involves an individual set of economic and production alternatives. While it’s impossible to guarantee what the future holds, it’s worthwhile to consider the best information we have to plan management decisions. The more accurate and in-depth your information, the clearer your decision-making will be. Almond growers have faced huge production challenges in the past, and found innovative ways to grow and improve through them.

For more details on these projections and research:

- Zhao et al (2020) “Assessment of climate change impact over California using dynamical downscaling with a bias correction technique: method validation and analyses of summertime results” Climate Dynamics. 54:3705–3728 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-020-05200-x

- An interactive map of how climate is expected to change in different ways and different areas of California: https://cal-adapt.org/tools/extreme-heat/

- Pathak et al (2021) “Impact of climate change on navel orangeworm, a major pest of tree nuts in California” Science of The Total Environment. 755 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142657

Leave a Reply