Clarissa Reyes, UCCE Orchards Staff Research Associate, Butte, Glenn, & Tehama

Luke Milliron, UCCE Orchards Advisor, Butte, Glenn & Tehama

Dr. Themis Michailides, UC Davis Plant Pathologist at the Kearney Ag Research and Extension Center

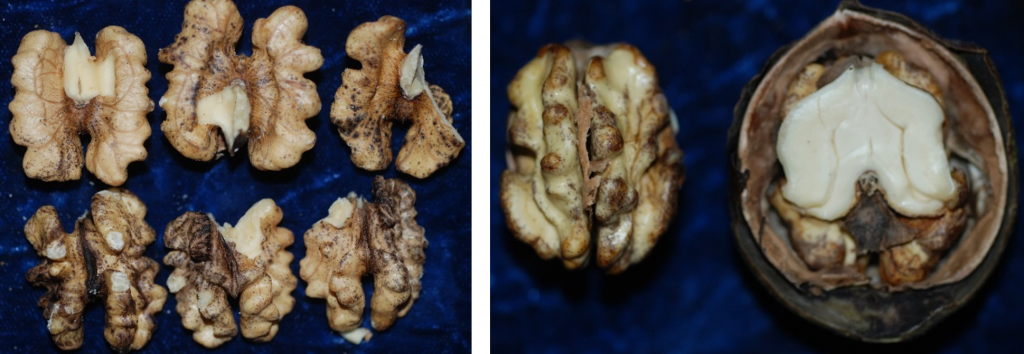

Photo 1. In the past five to six years there have been increased reports of walnut mold. Right photo: stained regions on the kernel are covered by loose mold mycelia. Photos courtesy of Dr. Themis Michailides.

What is walnut mold?

Growers and processors have reported elevated mold levels in harvested walnuts to farm advisors, which has resulted in pathology sample submissions to Dr. Themis Michailides, UC Davis Plant Pathologist (Photo 1). Although Botryosphaeria and Phomopsis (BOT) can cause walnut mold, most walnut mold develops from Fusarium and Alternaria species. Furthermore, walnut mold spray timing is later than BOT prevention spray applications and therefore your fungicide program for BOT will not control mold. Walnut mold does not begin to develop until the hull completes maturity and begins to split, long after most BOT-controlling sprays have been applied. Before these alerts and ensuing research, not much was known about managing mold in walnut.

Because of increased mold reports, the California Walnut Board has funded Dr. Michailides to investigate the management of walnut mold. Although all possible predisposing factors have not yet been investigated, conditions that compromise the integrity of the hull, such as walnut blight, sunburn or insect-damage can serve as an entry point for mold fungi.

Secondary blight predisposes nuts to mold:

Secondary walnut blight (Xanthomonas arboricola pv. juglandis) infections that do not penetrate to the kernel nor result in nut drop, can create an entry for not only moth pests, but for the mold caused by Fusarium and Alternaria species. These infections are a specific type of walnut mold called brown apical necrosis (BAN), named because the black blighted lesions at the apical end (aka: stylar – floral remnant) of the fruit, that turn brown following fungal colonization (Photo 2). As the fungal infection expands under the hull, the hull is decayed and the infection spreads to the kernel, most likely through the apical end. It stands to reason that improved walnut blight management, particularly of secondary infections, will lead to less BAN although this has not yet been studied. More on walnut blight best management practices in our article on Walnut Blight Management.

Photo 2. Brown Apical Necrosis (BAN) mold infections in Ivanhoe. Photo courtesy of Dr. Themis Michailides.

Predisposing factors and cultural controls for mold:

Practices that help maintain hull integrity are part of the pre-hull split management of walnut mold. One predisposing factor is sunburn, with mold commonly isolated from the sunburnt side of developing walnuts. Freeze damaged trees with less protective foliage are at high risk of sunburn and subsequent mold infection. Higher incidence of mold has also been found in insect infested nuts. Thus, controlling sunburn and insect damage will also help keep down mold infections. Finally, a critical management practice is timely shake and pick up. Bill Olson (UCCE Butte Advisor Emeritus) previously showed that mold and other quality problems increase the longer walnuts remain both on the tree and especially on the ground. Picking up the same day as shaking is a critical best practice for overall quality and grower returns, particularly for non-Chandler blocks.

Some varieties, such Ivanhoe and Livermore are more susceptible to mold than others, and therefore more diligent attention to mold management may be required. In earlier research, higher incidence of mold was discovered in walnut varieties with larger openings at the stem end and larger sized nuts.

New findings 2021.

Fungicide1 management for mold, 2019-2021:

In a 2019 trial using Chandler located in Butte County, the fungicide Rhyme (flutriafol) was tested because of its short preharvest interval (PHI). A single spray at either 30 or 60% hull split, reduced mold incidence by over 73%. In 2020, in the same orchard, two sprays with Rhyme, one at 3 weeks before hull split and the second at 20-30% hull split, resulted in 7% mold while the untreated control had 13% mold. However, this difference was not statistically significant. In 2021, a spray 2 weeks before hull split (HS), 1 week before HS, a spray at 20-30% HS, and 3 sprays at all 3 dates, significantly reduced mold (by 57-72%) in comparison with the untreated control. There were no differences among the treatments, an indication that one spray should be sufficient in reducing mold significantly.

New research on infection and control at bloom timing, 2020-2021: A second year of data collection further bolstered the conclusion that most mold infections start at the stylar end (aka: floral remnant) of the nut. These findings reinforce the contention that some infections by the mold fungi might start at bloom time. To determine if this could be a cause, bloom spray trials were initiated in 2021 and were repeated in 2022. In a trial using Tulare walnuts in Tulare County, a bloom spray gave similar control of mold as the 3 week and 1 week before hull split sprays and lead to significantly lower mold than the unsprayed control (evaluation by Diamond Foods). The same treatments applied using nearby Chandler showed no significant differences between the various spray timings and the unsprayed control trees. Please stay tuned for further information from the 2022 trial.

More efficacy testing of various chemical controls for walnut mold are planned and these results will be reported at UC IPM.

1Mention of pesticides and spray timings do not constitute a pesticide recommendation; it is merely the sharing of research results. Always follow the pesticide label and consult with your PCA.

Leave a Reply